Feb. 24, 2023

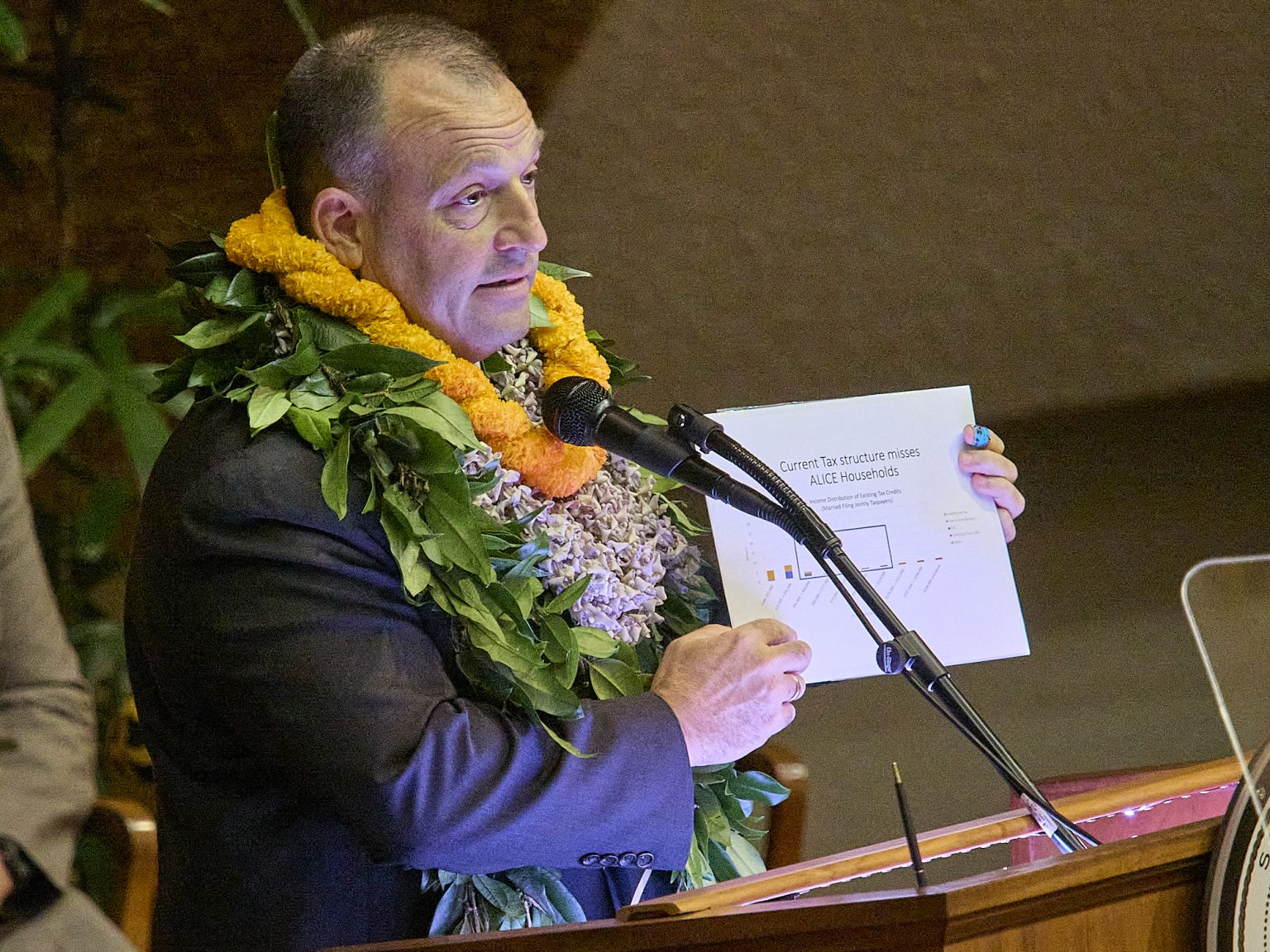

When arguing there’s a flaw in Gov. Josh Green’s tax policy to help middle- and lower-income households, University of Hawaii economist Dylan Moore zeroes in on a family of four on Oahu that illustrates Moore’s point about tax policy cliffs.

Such cliffs occur, Moore says, when a benefit suddenly is taken away because income exceeds some arbitrary threshold established by a policy. The governor’s proposal, known as the Green Affordability Plan, is full of cliffs, Moore says.

“It’s a lot more common than people realize,” said Moore, who studied phenomena like tax cliffs and their effects on human behavior while earning his doctorate at the University of Michigan.

Green administration tax officials say they’re open to fixing the cliff problem, but that it will be up to lawmakers to tweak bills now making their way through the legislative process.

The anonymous family of four in Moore’s recently published analysis illustrates the concern about cliffs.

The father, a military veteran, earns $58,960 annually working as a civilian engineer for a defense firm, according to a questionnaire submitted to the U.S. Census Bureau, which Moore found by combing through data. The mother, meanwhile, takes care of their two children, an 11-year-old boy and 14-year-old girl, and is pursuing a graduate degree.

According to Moore, the family is a classic ALICE family: asset limited, income constrained, employed – working-class with little financial breathing room. Green’s plan would provide $300 million annually for working households through an array of benefits including tax credits for things like food, child care and rent.

“Our plan takes the necessary steps to strengthen the health of ALICE families and communities,” Green said in his inaugural State of the State speech. “The Green Affordability Plan cuts taxes and provides tax relief annually for the people that need it most.

“This will help us get money into the pockets of working families so that they can purchase essential goods and services like food, medicine, and housing, which will in turn stimulate our economy,” he continued.

But according to Moore, there’s one problem: under Green’s plan, if the ALICE mother in Moore’s analysis were to start a small business or side hustle earning as little as $1,100 a year or just over $90 a month, it would actually reduce the family’s disposable income by $2 a year because of a cliff-like drop in tax credits and benefits.

Moore stressed that the family would be better off with Green’s plan than without it, regardless of whether the mother brought in the extra income. But under Green’s plan, taking on the extra income would mean a hit to the family’s bank account, Moore says.

“The cause of this perverse outcome is a large cliff created by the GAP,” Moore writes in an analysis published on the University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization website. “When this family’s income goes from $59,999 to $60,000, they fall off the cliff, losing $280 of Food/Excise Tax Credit money and $400 in Low-Income Renters’ Credit money.” Additional tax consequences would eat up the rest of the $1,100, Moore said.

The cliff eliminates any extra income the family might have gotten from the mother starting her business.

“Consequently, for this family, the GAP creates a powerful disincentive to earn additional income,” Moore wrote.