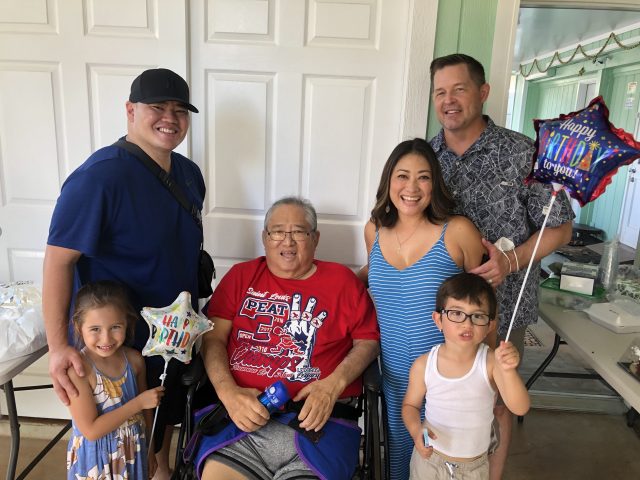

Photo: Michele Mueller | Article: Anita Hofschneider

To view on publisher's website, Click Here.

For the past two weeks, Barbara Tom has been at her wit’s end. She was worried on Aug. 11 when her 73-year-old brother went to the emergency room at The Queen’s Medical Center in West Oahu and tested positive for Covid, even though he’d been vaccinated.

She was even more concerned when he was discharged that day back to his adult foster care home, and a few days later when his caregivers there tested positive for the virus as well.

But her biggest frustration has been the difficulty in finding her brother, Paul Mikami, a ride to and from his dialysis treatments. The blood filtering treatment must be performed three times per week to ensure his kidneys function properly, but he has had to miss some appointments because he couldn’t take the Handi-Van while Covid positive.

Tom made call after call, trying to find someone who would help her brother. Not just any car would do — her brother is an amputee and unable to stand by himself, requiring a wheelchair and a Hoyer lift or gurney. She was relieved when the dialysis center helped her get transportation for two separate treatments. But it wasn’t enough.

He got so sick from lack of dialysis last week that he ended up back in the emergency room, where he remains hospitalized in Pali Momi Medical Center. He’s now one of more than 2,000 patients filling Hawaii’s hospitals and pushing the state’s medical infrastructure to its brink.

Hawaii’s pandemic has exacerbated existing disparities in Hawaii across gender and race. People with disabilities also have fallen through the cracks.

Kiriko Takahashi from the University of Hawaii Center for Disability Studies says given how diverse the community with disabilities is — including not only physical but intellectual disabilities — the pandemic has been a mixed bag.

Some have benefited from working from home and more remote events, she said. But others have had a higher risk of complications from Covid and struggled to get both information about the pandemic and access to basic medical care.

Vaccine access also has been a struggle for residents confined to their beds, some of whom are just now getting the shot even though they’ve been eligible for months.

Catherine Pirkle, an assistant professor of health policy and management at the University of Hawaii, said the current health care system wasn’t designed to help people with complex care and chronic conditions. Then came the pandemic.

“It’s put so much pressure on the system that where there were already weaknesses, those weaknesses are where we are seeing fractures,” she said.

What’s frustrating to Pirkle about Tom’s experience is that it was avoidable.

“If you look right now the last thing we want is any more pressure on our health care system,” she said. “It is quite perverse that we would have essentially a system that incentivized using an ambulance versus supporting the transportation to get to care that would keep this person out of the emergency room.”

In-Home Vaccinations

Some of the gaps in care for disabled people are in the process of being addressed. All Hawaii counties are offering free in-home vaccinations for homebound people, which the state and its partners started advertising in print in late July.

Diana Carter, 76, has been eligible for a Covid vaccine since January. But until this month, she didn’t know she could get one at home, where she has been largely confined following a stroke four years ago.

She really wanted a vaccine but knew she couldn’t physically maneuver to one of the major sites.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do,” Carter said. “Nobody knew, if you were homebound, how you were supposed to get it.”

It wasn’t until after the advertisements ran in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that a friend told Carter she could get the shot without leaving her bed.

In mid-August, a team of Waikiki Health and Hawaii Disability Rights Center staff drove to Carter’s home in Kaneohe and gave her the shot. Carter, happy to get the vaccine, talked animatedly about her career as a performer before her medical problems cut her dancing short.

“I’m not past my prime as a tap dancer,” she told the team helping her get inoculated, calico cat Rosie curled up on her lap.

After getting the shot, Carter felt a palpable sense of relief. So did her caregiver, who said he’d been wondering for months if it was possible for someone to come vaccinate her.

Brooks Baehr, spokesman for the Department of Health, said vaccinations on Oahu are being scheduled one or two weeks in advance, and the in-home program has the capacity to vaccinate about 50 people on Oahu each week.

The week of July 25, the state and its nonprofit partners administered 24 in-home shots on Oahu. The following week, there were about 60 in-home vaccinations.

Gaps In Care

But not all needs are being met. Tom, 72, is no stranger to crisis management. A former public health nurse who currently runs a social service organization, she’s plugged into what resources are available statewide for people like her brother.

As his condition worsened, she called all of them. She called 211 and was told to call a taxi service for her brother. She called the taxi service, and they said no way are they taking someone who is Covid positive.

Tom called the Handi-Van, which her brother usually takes to dialysis, and staff said they aren’t taking Covid patients either.

She called the state’s CARES line, which last year was marketed as a helpline for Covid patients. She said she left a voicemail and never heard back. The general public is now being discouraged from calling the line.

She called HMSA and Medicare, the Department of Health and the city. She got a quote for $800 to $1,000 for a single dialysis trip. She and her niece and her niece’s husband discussed whether they could afford it, and debated buying a used truck instead.

“There was just all this runaround,” Tom said. “I just didn’t know who to believe and what was going to happen.”

Aloha United Way told Civil Beat the 211 line refers disabled people to three transportation services but none accept Covid patients, adding that people with medical emergencies should call 911. The city recommended that too, and said Covid patients with disabilities should use private transportation.

HMSA said it provides transportation to and from dialysis only for Medicaid patients, not members or Medicare Advantage patients. Even then, finding willing drivers is hard.

“Due to the high demand for transportation services statewide, many of our partners have reported very limited availability,” said Christine Hirasa from HMSA.

She added that American Medical Response helps but is also busy with emergency services. Speedy Bailey, the company’s regional director, said the price of transporting a Covid patient depends on how long the trip is, but a three to four mile ride typically costs $600 to $800 round trip.

Need For Prevention

As Tom and her family struggled to find transportation, Mikami got sicker and sicker until his caregiver had to call an ambulance to take him to the emergency room. That, insurance would cover, Tom was assured.

She believes the situation could have been avoided if he had been able to get into an isolation and quarantine room as soon as he left Queen’s.

A spokeswoman from Queen’s said the hospital can’t comment on individual cases but that the health and safety of their patients and caregivers is their highest priority. Queen’s West recently declared an internal state of emergency because it’s so full of patients.

Baehr from the Department of Health said they just added 100 isolation and quarantine rooms on Hawaii island and 13 more on Maui. But Honolulu still has only 64 rooms for Covid patients, not enough for people in congregate living situations.

Officials have previously cited tourists filling up hotel rooms, lack of funding and the transmissibility of the delta variant as reasons for not providing more rooms.

A Handi-Van dedicated to Covid patients would have helped too, Tom said.

“These are gaps in services that we need to fill for not only the disabled but for those who don’t speak English,” she said. “We need to do prevention at the front end so that we don’t have patients going to the hospital unnecessarily.”

Even now, she’s trying to figure out where her brother will go after he’s discharged. His caregivers at the adult foster care home are still sick and don’t want him to go back yet. Tom says Pali Momi threatened to report the adult foster care home to Adult Protective Services if they refused to take him, prompting the home to release her brother from their care entirely.

Kristen Bonilla from Pali Momi Medical Center said the hospital “works closely with patients, their families and caregivers to ensure appropriate care and resources are available to them after they are discharged from the hospital.”

So far, Tom hasn’t had any luck. She found a skilled nursing facility that accepts Covid patients. But the program is just getting up and running; for now, they aren’t accepting anyone on dialysis.